Upgrade & Afterlife

Upgrade & Afterlife is the third album by Gastr del Sol.

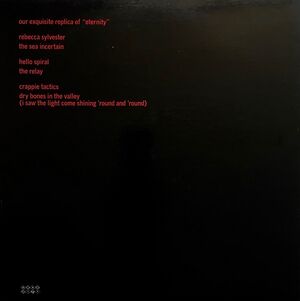

Track listing

| Title | Length | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | A. | "Our Exquisite Replica of 'Eternity'" | 8:26 |

| 2. | B1. | "Rebecca Sylvester" | 3:53 |

| 3. | B2. | "The Sea Incertain" | 6:12 |

| 4. | C1. | "Hello Spiral" | 10:40 |

| 5. | C2. | "The Relay" | 5:49 |

| 6. | D1. | "Crappie Tactics" | 1:48 |

| 7. | D2. | "Dry Bones in the Valley" | 12:27 |

Personnel

Cover art

The cover photo is "Wasser Stiefel" (1986) by Roman Signer.

See also: Signer's fountain in Munich, "Zwei Paar Stiefel" (2004)

Retrospectives

I would say that each [Gastr del Sol] album was really considered as a distinct project. So, for instance, Upgrade and Afterlife, we knew that there would be this firewall at the beginning of it [the dissonant, discomforting "Our Exquisite Replica of 'Eternity'"], that people had to decide whether they were going to scale, or wade through.

Reviews

NME

Tom Cox[2]

Isn't this drone-rock business just getting a little bit too easy? All you need is a few noises resembling a shark's breathing pattern, a member of Tortoise roped in to produce, and - huzza! - you're off and running. A gaggle of thoughtful underground types will follow your every move, commenting on your 'fabulous deconstructive post-rock textures, daaahling', in the process overlooking the fact that you are probably very boring.

A cushy predicament indeed. The likes of Gastr Del Sol - original Chicagoan 'innovators', allegedly - to this day basically make records intended to be a thoroughly 'intricate' and 'complex' experience. A bit like building a life-size replica of York Minster out of Lego. And ultimately as pointless, if not as colourful. 'Upgrade And Afterlife' sees Gastr once again going to vast lengths to deconstruct the boundaries of conventional rock. So vast, in fact, that they completely forget to reconstruct them into any vaguely palatable form or shape. Instead, we're left puzzling over the progressive qualities of five minutes of stripped-down, deserted, 1mph piano or searching desperately for any semblance of enterprise in the sound of an unaccompanied exploding calculator or - mostly - scrambling for the nearest Tiger or Quickspace Supersport single and a much-needed reminder that droning can be FUN.

But the Adult-Oriented Post Rock experience has hardly begun. As the limp, beard-wearing vocals slouch in on 'The Relay' there is only one option left - you must throw the nearest futuristic toy at your stereo and tell Gastr Del Sol to 'nick off' in an extremely loud voice. This labyrinth of noodly tedium has become too much.

The Wire

August 1996

Simon Hopkins

The mercifully prolific guitarist-inventor Jim O'Rourke continues his one-man mission to save the reputation of the world's most overplayed instrument. Lip service is paid elsewhere to the curious intersections of American folk musics and experimental/art music, but O'Rourke has a rare talent for actually making music from their congruence. He can summon up what Peter Guralnick has identified as the absolute sense of wonder at first hearing, say, Robert Johnson's recording as a college kind in the 60s—a sense of the music (now horribly ubiquitous, and horribly watered down) as somehow unspeakably alien.

Upgrade And Afterlife contines O'Rourke's ongoing project with David Grubbs. In common with the best US post-rock, this music wears its influences on its sleeve yet remains impossible to pin down. Grubbs' beautifully skewed, minimal acoustic guitar and voice pieces—Kurt Weill as played by a train-hopping hobo with an Arto Lindsay hang-up—pop up between the LaMonte Young organ droning of "Our Exquisite Replica of Eternity" and the Faust-ish radio mangling of "The Sea Incertain". Elsewhere, "Hello Spiral" nods to both Slint, with its math rock electric guitar comping (and no one records guitar quite as viscerally as O'Rourke) and John McEntire's compelling jazz snare rhythms, then suddenly collapses into cacophonous feedback.

The album somehow crystallizes all this with the closing track, John Fahey's "Dry Bones in the Valley". Fahey's folk-brutalism has rightly been namechecked by the likes of McEntire of late, but here the despair behind the pretty guitar melody is thrown into relief by Tony Conrad's scraping violin lines. It's in the very best tradition of maverick American low/high-brow distinction-scrapping, and worth the price of the CD alone.

Artforum

October 1996[3]

Olivier Zahm

On the cover of Upgrade & Afterlife (Drag City), a pair of boots explode in an aqueous burst on the floor, as though the person solidly implanted in them had just disintegrated in this splash. Roman Signer’s image suits Gastr del Sol’s latest CD perfectly: the musical texture is unpredictable, its apparent simplicity giving way to sudden explosive bursts. Upgrade & Afterlife is shot through with musical luminaries: here, Chicagoans David Grubbs and Jim O'Rourke are assisted by such collaborators as Gene Coleman (on bass clarinet), Tony Conrad (violin), and Günter Muller (amplified percussion). Gastr del Sol’s musical universe is filled with juxtapositions, with the more or less peaceful coexistence between written and improvised parts, instrumental and vocal sequences, and acoustic and electronic manipulations. For three years, Grubbs and O’Rourke have constantly futzed the musical boundaries of the hybrid genre of “innovation,” one they seem to spontaneously reinvent; the band specializes above all in bringing together sources as disparate as rock, folk, and contemporary experimental music (especially Cage), as well as Satie, Stravinsky, atonal music, and the found noises of the street and the apartment. That said, Gastr del Sol’s particular brand of innovation bears more resemblance to funambulism than to any one of the band’s scholarly references. Even more than the duo’s previous releases, Upgrade & Afterlife balances on invisible wires: the more or less repetitive melodies and random tones seem to obey their own laws of musical gravity, until the passing sound of a boiling teakettle, some miked reverb, or even a few words sung by Grubbs sets the whole delicate thing crumbling, scattering in a space whose equilibrium is even more precarious and capricious.

When O’Rourke says that "every record has to be better than the last," you believe him, because he talks like a mountain climber: his is a high-altitude balancing act, and he aims even higher. In fact, as his art becomes more sophisticated, it simultaneously becomes more commonplace and simple, even more immediate. The sonorous chemistry announced by the word “Afterlife” is strange and paradoxical, for it certainly has something terminal about it, but something unthreatening and gentle as well. The other half of the equation, “Upgrade,” emphasizes the project’s luminosity and economy: Gastr del Sol seems to go less in the direction of performative virtuosity and more toward a sound that approaches triviality. On the CD, texture overrides the shock of the sound effects, as well as the silences and slow progressions found on earlier releases, to become clearer and more straightforward. It’s as if texture and melody were playing an elaborate game of hide-and-seek.

Certainly their most limpid album to date, Upgrade & Afterlife leaves the harsher and more violent aspects of most experimental music far behind to allow us to traverse a universe where the air becomes more rarefied the more easily you breathe: aptly enough, “Our exquisite replica of ‘eternity’” is the title of the first sequence.

The Sound Projector

1997[4]

Wonderful stuff this - though it wasn't an immediate grabber, I now deem it a highly crafted recording exhibiting consummate studio skill, very listenable, and a pleasingly deft combination of the story (songs) with the abstract (instrumentals). Jim O'Rourke is one half of this duo, which is why I decided to investigate - on the strength of his work with Faust. People can sometimes spout nonsense about 'imaginary movie soundtracks'. More apposite to a record like this is the phrase 'Movie for your Ears', coined by Frank Zappa for his 1969 LP Hot Rats. Zappa's proposal for making records this way should have been followed by more musicians, I feel. (Notwithstanding the 'Cinema of the Ear' series of music concrète minidiscs issued by Metam Kine in France; O'Rourke did one called Rules of Reduction, MKCD 009.) This Gastr record seems to having a shot at it. More than simply suggesting suitable cinematic images to accompany itself, it (like Hot Rats) pays close attention to light and shade, tonal colour balance, textures, and a highly developed feel for the linear progression of the whole recording - it's edited and ordered like a cinematic event, not just a loose affiliation of episodes (which isn't to say it's like a 1970s concept album in any way!). This is helped by the brilliant move of playing a John Fahey composition as the final track, played with loving care by O'Rourke and overlaid with lusciously managed sounds including the great Tony Conrad playing a slightly more approachable version of his minimal violin drones. Elsewhere the bizarre fragmentary songs delivered with a hesitant breathy vocal over a close-miked acoustic classical guitar evoke The Red Krayola. And the first track starts with a tasty chandelier-shattering organ chord, which edits into a sample of that brilliant melancholy trumpet solo from The Incredible Shrinking Man. This CD is undeniably precious and fragile, but so what?

Rough Guide to Rock

2003[5]

[...] In the wake of this profusion of activity, Gastr Del Sol struck gold with their next album, Upgrade & Afterlife (1996). With string contributions from Conrad, horns from Mats Gustafsson and Gene Coleman, plus O'Rourke's tape cut-ups and white noise squeals, the record offered a cinematic amalgam of layered textures and atmospheric mood swings. This particularly held true for the album's lengthy bookends: the opener, "Our Exquisite Replica of 'Eternity'", wheezes, cackles and, ultimately, bursts into a grand cry of horns; at the end of the set "Dry Bones In The Valley (I Saw The Light Come Shining 'Round And 'Round)" beautifully reworks a Fahey song and concludes with a hypnotic coda replete with a Conrad violin drone. Upgrade & Afterlife presented challenging musical concepts and juxtapositions in a fashion that was never overwhelming, rarely dull, and too darn lovely to be considered pretentious. [...] Considered by many to be Gastr's finest moment, Upgrade & Afterlife opens with an ominous, cackling drone and closes with a smooth, lulling drone. It also contains the duo's most beautiful song - a cover of John Fahey's "Dry Bones In The Valley" - and finest album cover: a striking photograph of water exploding forth from a pair of Wellington boots.

AllMusic

Nathan Bush[6]

Somewhere along the line, Upgrade & Afterlife's original concept -- a set of conventional song made up of "normal" chords and accessible melodies -- must have been abandoned. Instead, David Grubbs and Jim O'Rourke's fifth album as Gastr del Sol abounds with elliptical melodies, broken by silence and noise, that avoid resolution. The antithesis of a pop lyricist, Grubbs' elusive wordplay and vague, surreal imagery matches his music, particularly on "Rebecca Sylvester." Random noise interrupts throughout the album, bursting and seeping through song surfaces, wreaking havoc on the compositions. A fanfare of destructive screeches announces "Hello Spiral." On "The Sea Incertain," they emerge from the stops and starts of the piano's careful explorations, pushing the instrument out of focus and out of the picture. A paranoid hum underpins "The Relay and "Crappie Tactics." There is beauty throughout Upgrade & Afterlife, but it's almost entirely on Gastr's terms. Grubbs' gorgeous vocal melody on "The Relay" carries some of his most cryptic imagery. "Cooked corn in formaldehyde/Popcorn in an airtight jar," he sings, backed by a dissonant piano. The album's biggest surprises are its bookends: "Our Exquisite Replica of 'Eternity'" (an absurd opening statement) may someday be recognized as the perfect piece of film music, capable of communicating as much paranoia, suspense, and terror as a director could with his/her camera. It's an ominous drift fractured by shards of electronic feedback, breaking through and breaking down like static between alien stations before closing with mournful trumpets. Meanwhile, Jim O'Rourke's performance of John Fahey's "Dry Bones in the Valley" ends the album with pure fresh air, resolving every awkward moment offered up in the preceding 37 minutes. Joined by Tony Conrad, the pair embark on an exploration of the violinist's micro-tonal drones that follow the album into the sunset.

References

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/fearlessmakingof0000leec/page/223/mode/1up

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20000817203805/http://www.nme.com/reviews/reviews/19980101001116reviews.html

- ↑ https://www.artforum.com/columns/gastr-del-sol-202278/

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/CompleteWEB/page/n19/mode/2up

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/roughguidetorock0003unse/page/416/mode/2up

- ↑ https://www.allmusic.com/album/upgrade-afterlife-mw0000649022